Daryl LaFleur published the following interview with James Howard Kunstler on Northampton Redoubt this weekend. Kunstler is the author of The Geography of Nowhere, written “Because I believe a lot of people share my feelings about the tragic landscape of highway strips, parking lots, housing tracts, mega-malls, junked cities, and ravaged countryside that makes up the everyday environment where most Americans live and work.” We are reprinting a large excerpt from LaFleur’s interview with permission.

Last August Northampton Redoubt interviewed James Howard Kunstler,

noted author, social critic and a leading proponent of New Urbanism. He

spoke on infill development, specifically as it pertains to the

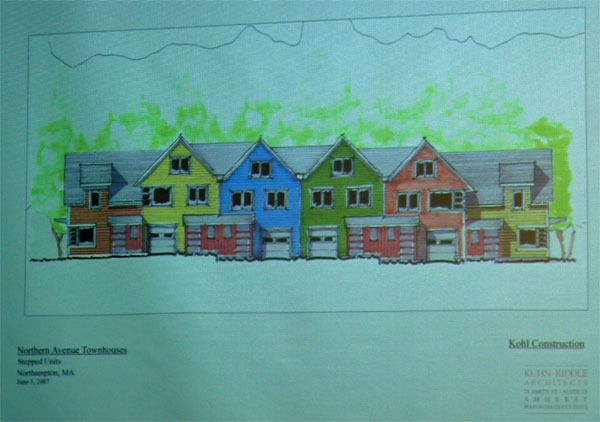

thirty-one unit Kohl condominium proposal off of North Street in

Northampton, which has since been amended to twenty-five units. Mr.

Kunstler did not have the benefit of viewing the Kohl proposal prior to

the interview, but he weighed in nonetheless.NR: Mr. Kunstler, is all infill good?

JHK:

There are many ways of looking at it okay, one way is this: that we are

now entering an era in which we are going to reactivate our existing

towns because the suburban project is over. We will be reactivating and

infilling our towns. What we’re seeing now is that in the early stages

of this we’re not very good at it. Over the last fifty years of putting

most of our investment in suburbia our skills have been lost. We’re

getting them back, but we have a ways to go. To some extent the New

Urbanists have been very helpful in retrieving the necessary principles

and methodology for doing this kind of work. We owe them a real bit of

gratitude for diving back into the dumpster of history and getting this

information, for example, (on) how to design mixed use urban buildings.What’s

really going on at the moment is that the architects have not kept up

with the urbanists. The urban design is getting back to a pretty good

normative level where we’ve rediscovered that you have to bring the

building out to the sidewalk edge, if it’s a downtown business

building. It has to relate directly to the street and the public realm

which is composed mostly of the street. And that you have to make a

provision for retail at the ground floor and other things upstairs. We

get that now; we’re doing that pretty well, at least in my town of

Saratoga Springs, (NY), which is a comparable caliber sort of town to

Northampton.What you’re seeing is that the architecture has

not really come back to this level of urban design. The architects are

still lost in the raptures of modernism, which includes an inability to

proportion buildings correctly or to ornament them with any kind of

conviction. One of the guiding principles of the modern experience in

modernist ideology is that you can’t do ornaments on buildings. That

has tended to persist and it’s still with us. At the highest level of

architecture, the highest levels of practice in architecture these

days, the big stars are still preoccupied with mystifying the public

and that’s exactly what we don’t need. We don’t need to confound

people’s expectations about how the building’s work or how they relate

to the public realm. In fact we need to reconnect the broken

connections. The architects are not helping at the moment although at

the non star level, the level that they’re practicing in Saratoga

Springs and perhaps over in Northampton, at the non star level they’re

not as preoccupied with making statements of mystification as much as

they are in New York (City) or Barcelona. But the lack of skills is

still obvious. We’ve had a very exuberant period of infill here

(Saratoga), with about seven to eight new buildings in the last

forty-eight months; almost all apartment buildings with retail on the

ground floor; they behave the way we want them to, the urban setting.

But the architecture really lacks conviction and grace.NR: In

Northampton we’ve had a couple projects in the past couple of years

downtown where they’ve taken previously developed sites and put in, as

you say retail on the first floor, dwellings on the second floor and

that isn’t really being argued. What is being argued is there’s a

proposal now to put in thirty-one condominiums in an urban forest

that’s right now very close to wetlands. This would be single use,

there wouldn’t be any frontage on the street; they are not creating a

traditional street with the faces of the buildings towards the street.

They’re creating basically parking lots in the forest and the backs of

the buildings would front the parking lot. You would drive down a

traditional street that’s been there for over a hundred years with

single or maybe two family homes, quaint homes, and it would culminate

in a thirty-one unit subdivision of row houses. And the city recently

rewrote its local wetlands ordinance to allow for encroachment up to

within ten feet of wetlands in the built up areas. The argument has

been not so much that infill in and of itself is good or bad but rather

is (in regard to) the design of this particular project going forward.JHK:

Yeah, it sounds pretty bad. I think that’s correct to say if the

proposal does not include the creation of a legitimate urban street

that relates to the building, if it’s just a tower in a parking lot.NR:

It is two or three story row house condominiums. There is no street per

se in the traditional sense. The streets now are dead-ends.JHK:

Well they need to create traditional streets and the town should make

it illegal to do any more cul de sac type development. Clearly that is

now something that we’re done with in America. For one thing it implies

that the thing is going to be automobile oriented. There is no question

that the car dependent period of our history is coming to an end. Now

what you’re seeing is an inability for us to let go of that idea. So

we’re still designing for it. I think the truth of the matter is it’s

over.NR: The argument in favor of these condominiums is that

it’s better to eliminate the in-town forest rather than to eliminate

the forest that’s in the outskirts of town.JHK: You end up

with a whole set of issues that relate to confusion over urban and

rural typology, which is to say, people end up being very confused

about what’s the town and what’s the country. They’ve got an impulse to

both urbanize the rural edge and then to try to ruralize the affect of

urbanizing the rural edge. All their impulses are confused and I see

this all over the place.NR: Unfortunately infill has been called, “good,” simply by the use of that term.

JHK:

People have also co-opted the term New Urbanism and then done

half-assed versions of it. Just co-opting a name doesn’t make it good.NR:

We’ve talked about the design but the buildings are designed poorly and

they don’t match the existing character of the neighborhood. It means a

lot more traffic and a lot more asphalt. When we’re going to be

building to within ten feet of wetlands it generally doesn’t account

for one hundred year floods and what homeowners might end up living

with after the property is conveyed to them…

See also:

Our Ad in Today’s Gazette: A Review of Our Objections to the Kohl Condo Proposal

Smart Growth vs. “Smart Growth”

Some claim that because Kohl’s proposed condos are within walking distance of downtown and have a high density, they are a good example of Smart Growth. However, there’s more to it than that, according to the Urban Land Institute (ULI).

True Smart Growth respects green infrastructure, such as trees and wetlands. These greenspaces filter the air, reduce the urban heat island effect, enhance property values and moderate stormwater flows, and they do it inexpensively. Urban greenspace is associated with improved physical and mental health and greater social cohesion in neighborhoods.

True Smart Growth preserves a community’s character, unlike development that “bears little relationship to a community’s history, culture, or geography.” ULI says homebuyers are increasingly attracted to vernacular and historical house styles that characterize their immediate area or region. Quoting Jim Constantine, a market specialist who does “curb appeal” surveys for developers, “Consumers are turned off by cookie-cutter subdivisions and the homogenous look of houses.” Unfortunately, that’s exactly what Kohl Construction is offering the neighborhood.

Smart Growth vs. “Smart Growth”

Smart Growth, in its full flower, contains numerous protections,

safeguards, checks and balances….

The problems with Kohl’s condo proposal include:

* It threatens green infrastructure by putting roads and structures as close as 35 feet or less to a wetland. Scientific evidence

indicates that substantial disturbance within 50 feet puts wetland

ecology at risk and threatens water quality. In addition, the condos

themselves appear to be at risk of flooding.

* It goes against the existing character and diversity of housing stock in the neighborhood by offering a monotonous, cookie-cutter design scheme with little sense of place.

* As Daryl LaFleur

observes, “the Kohl North Street area development proposal includes row

house condominiums set to the rear of parking lots, not free standing

detached single family homes that front the ‘street’, which would

better match the existing neighborhood and is also a tenet of Smart

Growth.”

Smart Growth is most palatable when it’s

implemented as a whole. When public and private actors are allowed to

cherry pick aspects that suit their convenience, the “Smart” can be

lost.

Grasping the Sustainable Northampton Vision: We Need Pictures

In all the 78 pages of the draft Sustainable Northampton Plan

(PDF), there is only a single graphic. It’s the Future Land Use Map, an

abstract, top-level view of the city. That’s unfortunate, because

without drawings, pictures and illustrations, it’s difficult to

envision how the Plan will change the look and feel of

Northampton. James Kunstler, an advocate of New Urbanism, discusses

this problem in “Home From Nowhere”, published in the September 1996 issue of The Atlantic Monthly…

Tailoring Infill and the New Urbanism to Northampton

The Atlantic Monthly had an excellent article on zoning and new

urbanism in September 1996: “Home From Nowhere” by James Kunstler. This

article appears to contain many of the ideas that support the concept

of infill. It can be found with related articles at http://www.theatlantic.com/politics/sprawl.htm

(a paid subscription may be required to access some articles)

Kunstler provides an example of a downtown streetscape that worked:

“Where I live, Saratoga Springs, New York, a magnificent

building called the Grand Union Hotel once existed. Said to have been

the largest hotel in the world in the late nineteenth century, it

occupied a six-acre site in the heart of town. The hotel consisted of a

set of narrow buildings that lined the outside of an unusually large

superblock. Inside the block was a semi-public parklike courtyard. The

street sides of the hotel incorporated a gigantic verandah twenty feet

deep, with a roof that was three stories high and supported by columns.

This facade functioned as a marvelous street wall, active and

permeable. The hotel’s size (a central cupola reached seven stories)

was appropriate to the scale of the town’s main street, called

Broadway. For much of the year the verandah was filled with people

sitting perhaps eight feet above the sidewalk grade, talking to one

another while they watched the pageant of life on the street. These

verandah-sitters were protected from the weather by the roof, and

protected from the sun by elm trees along the sidewalk. The orderly

rows of elms performed an additional architectural function. The trunks

were straight and round, like columns, reiterating and reinforcing the

pattern of the hotel facade, while the crowns formed a vaulted canopy

over the sidewalk, pleasantly filtering the sunlight for pedestrians as

well as hotel patrons. All these patterns worked to enhance the lives

of everybody in town-a common laborer on his way home as well as a

railroad millionaire rocking on the verandah. In doing so, they

supported civic life as a general proposition. They nourished our

civilization.“When I say that the facade of the Grand Union

Hotel was permeable, I mean that the building contained activities that

attracted people inside, and had a number of suitably embellished

entrances that allowed people to pass in and out of the building

gracefully and enjoyably. Underneath the verandah, half a story below

the sidewalk grade, a number of shops operated, selling cigars,

newspapers, clothing, and other goods. Thus the street wall was

permeable at more than one level and had a multiplicity of uses…”

Kunstler

goes on to suggest we should learn from the human-scaled success of

places like Nantucket, St. Augustine, Georgetown, Beacon Hill, Nob

Hill, Alexandria, Charleston, Savannah, Annapolis, Princeton, Greenwich

Village and Marblehead.

Kunstler discusses managing density to avoid congestion:

“Houses may be freestanding in the new urbanism, but their

lots are smaller than those in sprawling subdivisions. Streets of

connected row houses are also deemed desirable. Useless front lawns are

often eliminated. The new urbanism compensates for this loss by

providing squares, parks, greens, and other useful, high-quality civic

amenities. The new urbanism also creates streets of beauty and

character. This model does not suffer from congestion. Occupancy laws

remain in force — sixteen families aren’t jammed into one building, as

in the tenements of yore. Back yards provide plenty of privacy, and

houses can be large and spacious on their lots. People and cars are

able to circulate freely in the network of streets. The car is not

needed for trips to the store, the school, or other local places. This

pattern encourages good connections between people and their commercial

and cultural institutions…“In order for a street to achieve

the intimate and welcoming quality of an outdoor room, the buildings

along it must compose a suitable street wall. Whereas they may vary in

style and expression, some fundamental agreement, some unity, must pull

buildings into alignment. Think of one of those fine side streets of

row houses on the Upper East Side of New York. They may express in

masonry every historical fantasy from neo-Egyptian to Ruskinian Gothic.

But they are all close to the same height, and even if their windows

don’t line up precisely, they all run to four or five stories. They all

stand directly along the sidewalk. They share materials: stone and

brick. They are not interrupted by vacant spaces or parking lots. About

half of them are homes; the rest may be diplomatic offices or art

galleries. The various uses co-exist in harmony. The same may be said

of streets on Chicago’s North Side, in Savannah, on Beacon Hill, in

Georgetown, in Pacific Heights, and in many other ultra-desirable

neighborhoods across the country.”

Envisioning Sustainable Northampton: Notre Dame Urban Design Presentation – Video and Handout

Envisioning Sustainable Northampton: Notre Dame Urban Design Presentation – Slides