Northampton’s Office of Planning and Development has made the new Proposed Local Natural Hazards Mitigation Plan (PDF) available for public review. The Planning Board will hold a public hearing on this plan on November 13, 7pm, in City Council Chambers, 212 Main Street.

We compared the new Plan to the existing one, which the City Council signed off on in 2004. We gave special attention to wetlands regulations. Wetlands play a valuable role in mitigating both floods and droughts.

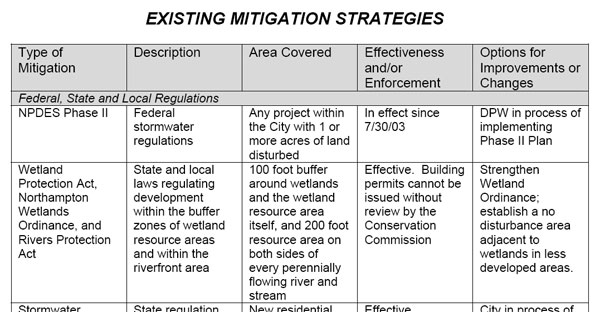

The 2004 Plan specifically mentions the regulation of development within 100-foot buffer zones around wetlands as an effective flood mitigation strategy. It even suggests the Wetland Ordinance should be strengthened:

Unfortunately, the City Council voted 7-2 in 2007 to permit development in multiple districts to encroach as close as 10 feet to wetlands. In a rapid shift of priorities, facilitating urban infill was now deemed more important than flood mitigation, water pollution control, or urban greenspace. The proposed condo development off North Street is a good example of a project that relies on the narrowed buffer zones.

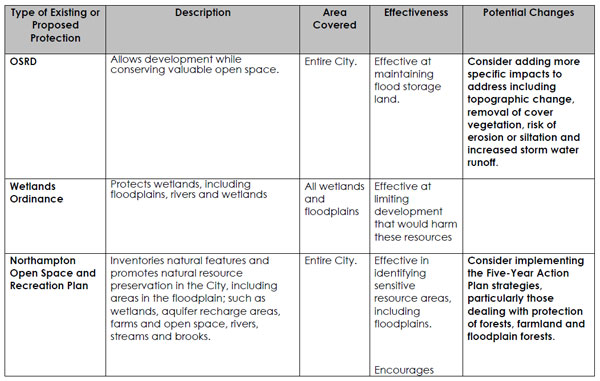

The 2008 Hazards Mitigation Plan reflects the weakened wetlands protection by leaving out all mention of 100-foot buffer zones. Instead, it merely refers readers back to the Wetlands Ordinance and continues to claim it is “effective at limiting development that would harm these resources.” From page 60:

The claim that allowing development within 50 feet of wetlands can still give effective protection does not bear up under scientific scrutiny. As Hyla Ecological Services noted in 2007:

“Buffers of less than 50 feet in width are generally ineffective in protecting wetlands. Buffers larger than 50 feet are necessary to protect wetlands from an influx of sediment and nutrients, to protect wetlands from direct human disturbance, to protect sensitive wildlife species from adverse impacts, and to protect wetlands from the adverse effects of changes in quantity of water entering the wetland…” (Castelle et al., ‘Wetland Buffers: Use and Effectiveness’, 1992)

“Buffer function was found to be directly related to the width of the buffer. Ninety-five percent of buffers smaller than 50 feet suffered a direct human impact within the buffer, while only 35% of buffers wider than 50 feet suffered direct human impact. Human impacts to the buffer zone resulted in increased impact on the wetland by noise, physical disturbance of foraging and nesting areas, and dumping refuse and yard waste. Overall, large buffers reduced the degree of changes in water quality, sediment load, and the quantity of water entering the adjacent wetland.” (Castelle et al., 1992)

More recently, the Environmental Law Institute issued a Planner’s Guide to Wetland Buffers for Local Governments which said (emphasis added):

Depending on site conditions, much of the sediment and nutrient removal may occur within the first 15-30 feet of the buffer, but buffers of 30-100 feet or more will remove pollutants more consistently. Buffer distances should be greater in areas of steep slope and high intensity land use. Larger buffers will be more effective over the long run because buffers can become saturated with sediments and nutrients, gradually reducing their effectiveness, and because it is much harder to maintain the long term integrity of small buffers. In an assessment of 21 established buffers in two Washington counties, Cooke (1992) found that 76% of the buffers were negatively altered over time. Buffers of less than 50 feet were more susceptible to degradation by human disturbance. In fact, no buffers of 25 feet or less were functioning to reduce disturbance to the adjacent wetland. The buffers greater than 50 feet showed fewer signs of human disturbance…

…The Environmental Law Institute’s (2003) review of the science found that effective buffer sizes for wildlife protection may range from 33 to more than 5000 feet, depending on the species…

Enacted local government buffer ordinances show a wide range of wetland buffer dimensions. The lowest we found was 15 feet measured horizontally from the border of the wetland, with the highest approximately 350 feet. Several ordinances set 500 feet as a distance for greater regulatory review of proposed activities, but do not require nondisturbance at this distance. Often the ordinances provide a range of protections, with nondisturbance requirements nearest the wetland and various prohibitions and limitations as the distance from the wetland increases. Among the ordinances we examined, the largest number of ordinances clustered around nondisturbance or minimal disturbance buffers of 50 feet or 100 feet, with variations (usually upward variations) beyond these based on particular wetland characteristics, species of concern, and to account for areas with steeper slopes.

Most striking in the ELI report is that some locales desire wider buffers in areas of intense land use to address the higher levels of pollution and runoff. By contrast, Northampton has its narrowest buffers in these areas.

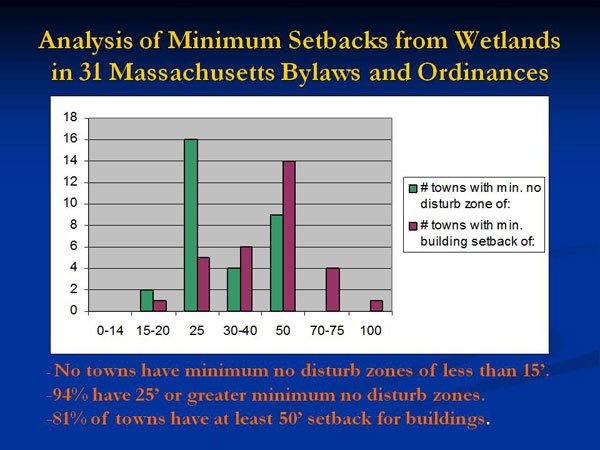

Earlier this year, NSNA engaged Hyla to compare Northampton’s new Wetlands Ordinance to the regulations in other cities across Massachusetts. Hyla found that Northampton is now an outlier. In the entire state, it’s hard to find anything similar to our 10-foot buffer zones for new development.

When arguing for the new Wetlands Ordinance in 2007, Bruce Young, Land Use and Conservation Planner, said it was necessary to allow homeowners to build small accessory structures (e.g. in-law apartments) on their property. We are sympathetic to this argument, but it’s a far cry from the 26 condos, new roads and parking lots that Kohl Construction wants to build in the North Street woods.

Here’s one suggestion for a better balance of interests in zoning districts URB and URC:

- No disturbance closer than 25 feet

- No more than 10% of that portion of the buffer zone that’s 25-50 feet from a wetland should be covered with impervious surface of any kind

- No structures closer than 50 feet EXCEPT

- At the discretion of the Conservation Commission, the landowner may build a structure in the portion of the buffer zone that’s 25-50 feet from a wetland, provided the structure covers no more than 5% of that portion of the buffer zone

Before the new Wetlands Ordinance took effect, the de facto standard for most of Northampton was that structures should be kept at least 50 feet away from wetlands, and disturbance within 50 feet should be minimized. We believe this standard was scientifically sound, in line with practices elsewhere in the state, and should largely be returned to.

Concentrating development in infill neighborhoods, intended to preserve contiguous open space in outlying areas, has an abstract appeal. However, it must be balanced against urban residents’ need and desire for nearby greenspace, and a respect for local conditions. Specifically, a large part of the built-up areas of Northampton are situated in low-lying areas. Flooding is a significant risk, even for structures outside the 100-year floodplain. To eat into Northampton’s natural flood protection system is unwise, as is a reliance on hard-to-maintain manmade stormwater management systems.

Other Passages of Interest in the Proposed Hazards Mitigation Plan

“Based upon previous data, it seems likely that there is a thirteen percent chance of minor or severe flooding occurring every year in Northampton. This is partly a function of the presence of the Connecticut River and the Mill River, both of which contain significant floodplain acreage in Northampton. The area within the 100-year flood plain still has a one (1) percent chance of a severe flood in any given year.” (p.27, emphasis added)

“Massachusetts is susceptible to hurricanes and tropical storms. Between 1851 and 2004, approximately 32 tropical storms; five Category 1 hurricanes, two Category 2 hurricanes and three Category 3 hurricanes have made landfall. To date, the Commonwealth has not experienced a Category 4 or 5 hurricane. Aside from direct hits from hurricanes and tropical storms, the Commonwealth is often affected by their extra tropical remnants as these storms move up the coast and out into the Atlantic Ocean. Since the destructive hurricane of 1938, four other major hurricanes have struck the Massachusetts coast in 1954, 1955, 1960, 1985, and 1991. The last hurricane to make landfall in New England was Hurricane Floyd, a weak category 2 hurricane, in November 1999. Therefore, it is forecasted that, Massachusetts, and the rest of New England, is long overdue for a major hurricane to make landfall. Based on past hurricane and tropical storm landfalls, the frequency of tropical systems to hit the Massachusetts coastline is an average of once out of every six years.” (p.28, emphasis added)

“Northampton Wastewater Treatment Plant – Hockanum Road— the flood control pumps, fairly old and showing signs of wear, are especially vulnerable to failure and, if they failed, could create severe damage to both the plant and the surrounding low lying neighborhood.” (p.45, emphasis added)

“Strict adherence should be paid to land use and building codes, (e.g. Wetlands Protection Act), and new construction should not be built in flood-prone areas.” (p.51)

“Stormwater drainage and infiltration systems must be designed to withstand 1, 2, 10 and 100 year storms in Northampton” (p.54)

“The Northampton Hazard Mitigation Committee identified the following area as being most vulnerable to the hazards associated with hurricanes: down[town] Northampton.” (p.69)

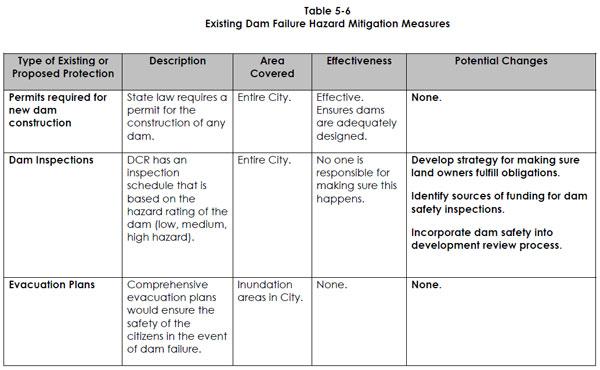

Dam Inspections: “No one is responsible for making sure this happens.” (p.92, emphasis added)

“In regards to the Northampton Open Space and Recreation Plan, implement the Five-Year Action Plan strategies, particularly those dealing with protection of forests and farmland. This mitigates flooding damage through providing the city with a natural buffer that would work to absorb floodwaters and rainwater while preventing development from increasing impervious surface area—large areas of impervious surfaces have been documented to worsen storm surge cycles and accelerate the flow of water.” (p.99, emphasis added)

“Major projects, except in the Central Business District must be designed so there is no increase in peak flows from the one (1) or two (2) and ten (10) year Soil Conservation Service design storm from pre-development conditions (the condition at the time a site plan approval is requested) and so that the runoff from a 4/10 inch rain storm (first flush) is detained on site for an average of six hours. These requirements shall not apply if the project will discharge into a City storm drain system that the Planning Board finds can accommodate the expected discharge with no adverse impacts…” (p.136)

See also:

City of Northampton, Memo from Mayor Clare Higgins to City Councilors, “FY 2009 Capital Improvements Program Recommendations” (12/4/08)

Bridge Street School – Detention Basin/Sewer Tie-in – $22,000

Repairing the three dry wells at Bridge Street School was ranked as the [Northampton Public Schools’] second highest priority. The wells are filled with silt and the ground water backs up into the building. The DPW has cleaned the wells but the problem still exists due to the lack of slope and the deteriorated condition of the wells.

Republican: “Hazard proposal finished” (11/1/08)

Flooding has been among the most costly natural disasters in recent years. The report cites the flood caused by Hurricane Floyd in 1999 that causes $900,000 in damages.

Northampton’s Flood and Natural Hazard Mitigation Plan: Floyd Flood Damage Reported Behind View Avenue; Avoid Building on Filled Wetlands

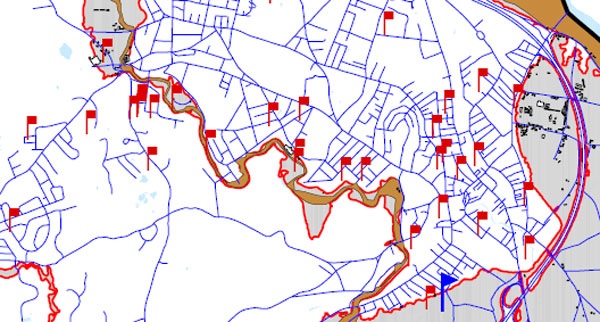

In the map below, the red flag behind View Avenue (the topmost flag) indicates a flood damage report from Tropical Storm Floyd (1999). This area is in the eastern portion of Kohl Construction’s proposed condo site, one of the more elevated portions. We infer that much of Kohl’s property may be at risk from heavy rainfall events.

…In general, a core problem for infill in Northampton is to avoid placing large numbers of people and structures in low-lying areas downtown that may be at risk for flooding. As the plan states, “In recent years, heavy rainstorms have caused significant problems in more urbanized areas as increased development inhibits proper drainage and existing or poorly maintained water systems cannot handle increased stormwater runoff.”

The Background of the plan states (emphasis added):

…Northampton can experience flooding in any part of the City. One great misunderstanding is the belief that floods only happen in the floodplain. With sufficient rain, almost any area will experience at least pockets of surface flooding or overland flooding. Overland flooding in rural areas can result in erosion, washouts, road damage, loss of crops and septic system back-ups. Heavy rain in the more urbanized parts of the City with extensive paved and impervious surfaces can easily overwhelm stormwater facilities resulting in localized flooding and basement damage. Stormwater flooding also contributes to water pollution by carrying silt, oil, fertilizers, pesticides and waste into streams, rivers and lakes. As the intensity of development continues to increase, Northampton will see a corresponding increase in serious stormwater problems. It is therefore important that the City as a whole, not just residents of the identified floodplain, address the need for mitigation. Flood and hazard mitigation is any preventive actions a community can take to reduce risks to people and property and minimize damage to structures, infrastructure and other resources from flood or other hazardous events. Hazard mitigation and loss prevention is not the same thing as emergency response. Some flood loss reduction can be achieved by components of response plans and preparedness plans, such as a flood warning system or a plan to evacuate flood prone areas. However, warning and evacuation deal only with the immediate needs during and following a flood event. Hazard mitigation is much more effective when it is directed toward reducing the need to respond to emergencies, by lessening the impact of the hazard ahead of time. (Massachusetts Department of Environmental Management 1997, 3)…

Analysis of Flood Hazards in Northampton (emphasis added)

…Major floods, such as those caused by heavy rains from hurricanes, and localized spot flooding can exceed the 100- and 500-year flood levels. In addition, many small streams are not mapped for their flood hazard… (p.18)

Flooding from stormwater runoff is a growing problem in every urbanized area and is caused by large amounts of impervious surfaces and by undersized or poorly maintained stormwater drainage infrastructure, including culverts and detention basins. Development not only creates more impervious surfaces, but it also changes natural drainage patterns by altering existing contours by grading and filling, sometimes creating unexpected stormwater flooding during heavy rains. Recently, the City of Northampton has seen flooding on Elm Street, along Church and Stoddard Streets, Bliss Street and Austin Circle due to undersized pipes and catch basins and lack of upstream detention that caused streams to jump their banks and flood roadways and properties.

Stormwater contributes to water pollution by carrying silt, oil, fertilizers, pesticides and waste into streams, rivers and lakes. Stormwater flooding also has the potential to cause considerable property damage because it occurs in areas of concentrated development… (p.19)

Environmental Limitations and Hazards Identification and Analysis (emphasis added)

Wetland related problems

Filled Wetlands

Many areas of the City were developed before the passage of the Massachusetts Wetlands Protection Act of 1972. Historically filled wetlands are commonly related to problems with wet basements, flooding, shifting foundations and failed septic systems. Development in historically filled wetlands should be discouraged through zoning in order to protect health and safety… (p.24)

Additional Natural Hazard Identification and Analysis (emphasis added)

…In addition to flooding from hurricanes and northeasters, Northampton is also susceptible to flooding from severe rainstorms and thunderstorms. The occurrence of significant rain events in the City has been increasing over the past several years.

Vulnerable Areas and Populations

The greatest impact in the City is felt in neighborhoods along rivers and streams. In recent years, heavy rainstorms have caused significant problems in more urbanized areas as increased development inhibits proper drainage and existing or poorly maintained water systems cannot handle increased stormwater runoff.

The most recent example is the flooding following Tropical Storm Floyd, a 100-year storm that occurred in September of 1999 which created severe localized flooding conditions in the small flashy watersheds of the City, especially along the Mill River and the historic Mill River (both within and beyond the mapped Zone A), and along Barrett Street Brook and Elm Street Brook (both outside of Zone A). This storm caused approximately $900,000 in property damage.

[Flood damage reports from Tropical Storm Floyd pepper downtown Northampton (1999). Note most of the red flags are outside the traditional 100-year floodplain. This is a sign that Northampton’s stormwater management systems are stretched even under the existing wetlands buffer zone regime. We object to ratcheting up the pressure on our in-town wetlands, a key part of our natural drainage system.]

Topographical Map Shows How Kohl Condo Proposal Will Eat Into a Rare Stand of Mature Trees in Downtown

The following view dramatizes the considerable amount of impervious surface already in the area, especially around King Street and the Coca-Cola plant. Kohl’s “infill” project will convert a significant amount of the remaining greenspace to impervious surface. The presence of Millyard Brook shows that this area serves as a natural sink for water in the neighborhood.

EPA: Wetlands and Flood Protection

Wetlands within and downstream of urban areas are particularly valuable, counteracting the greatly increased rate and volume of surface-water runoff from pavement and buildings…

The Economic Value of Wetlands: Wetlands’ Role in Flood Protection in Western Washington

Development practices that eliminate or compromise natural systems capable of controlling runoff appear to be exacerbating flooding problems in many areas. This highlights the importance of the remaining natural systems capable of attenuating flood flows, particularly wetlands, in the region’s defenses against increasingly destructive floods…

More than half of the wetlands that once existed in western Washington have been lost. Often the cause has been agricultural conversion, but today wetlands are increasingly at risk due to urban and suburban development. Western Washington is now one of the fastest growing regions of the country, and the remaining wetlands in rapidly developing areas are increasingly valuable for the flood protection they can provide. At the same time, the increasing pace and density of development is resulting in the natural wetlands systems that are capable of absorbing urban runoff becoming ever more fragmented, even as the need for flood protection grows ever more critical…

As Hurricane Threat Builds, Has Complacency Set In about Flooding?

Joe Bastardi, Chief Forecaster of the AccuWeather.com Hurricane Center, 2007:

“New England is fair game from now on until 2025, although the most frequent threats to the Northeast should be later in the run of the cycle… Since I believe we are in the early to middle stages of the AMO [Atlantic Multidecadal Oscillation], the backdrop of the late 30s is the canvas on which the hurricane forecast is being painted…”

Gazette: “Region’s storms going to extremes, report finds”

Extreme downpours and snowstorms are rising in frequency nationally, with the highest increases in New England…

Massachusetts saw a 67 percent rise in severe storms during [1948-2006], trailing only Rhode Island and New Hampshire…

…the top 10 severe storms in the state all occurred in the past decade…

…scientists expect that extreme downpours will punctuate longer periods of relative dryness, increasing the risk of drought…

Alewife Study Group: Impact of Development on Wetlands and Flooding

…As a direct result of development on the Alewife flood plain and its low elevation, there is periodic and significant flood damage in the surrounding communities. A 1981 study by the MDC found property damage in the Ale

wife area to be the highest of any portion of the Mystic River watershed of which it is a part.

UK Blog: Floods and Development, 7/23/07

…the LibDem Councillors, at a recent Cabinet meeting produced documents promoting an increase in “high density developments” in Teddington, Whitton and Twickenham. This is an issue I will come back to as a separate debate on planning, but given the flood risks in the area, should we really be concreting over our green spaces and further reducing drainage potential and increasing flash flood risk?

Gazette guest column: “Don’t ease controls on wetlands” (10/25/07, emphasis added)

[Alexandra Dawson, chair of Hadley’s Conservation Commission, writes,] …Northampton has adopted changes to its bylaws that limit the setback between development and wetlands in the business district to 10 feet, although it is obvious that 10 feet is not even enough space to accommodate the big yellow machines that do the building. It is true that a recent court decision indicates that wetlands ordinances (or conservation commission regulations adopted under them) should enumerate setbacks so that builders need not guess what will be required of them. Unfortunately, there is also case law stating that whatever is so established limits the commission’s discretion to ask for more unless there is a specific showing of why one proposal stands out from the others. If the setback in the ordinance is 10 feet, it will be very hard for the commission to justify a permit restricting building for 50 feet. For this reason, most eastern Massachusetts bylaws that contain setbacks start at 25 to 50 feet.

Is the Proposed Wetlands Ordinance Similar to Current Buffer Zone Policy? Judge for Yourself

Mike Kirby: “The Meadowbrook Chronicles Part One”

The Meadowbrook story has many important facets. Of particular interest to us are the consequences that can follow from building homes near wetlands…

The developers built 255 units of affordable apartments there. They crammed them in everywhere they could, pushing them up into the bluffs, and close to the creek and wetlands. No backyards to speak of. One third of the buildings were built within 50 feet of the wetlands, 63% of the buildings are within the customary 100 feet of wetlands.

None of the buildings have cellars under their apartments. If they have cellars, there are people living in them. The cellar floors in the basement apartments in Buildings #4 and #2 are lower than the surrounding swamp. Some slabs have cracks in them. People have been flooded out. No moisture-proof barriers between the surrounding earth and the foundations. Moisture and mold percolate up into people’s apartments via the chases that hold utilities. If you wonder why low-income children are afflicted with a whole host of respiratory diseases, you have to look no further than the children of the floor level and basement apartments of Meadowbrook…

Northampton Redoubt: Doug Kohl reduces “footprint” of subdivision proposal due to the discovery of vernal pools in the North Street area wetlands (9/12/07)

Daryl LaFleur writes:

When I asked about the possibility of basements flooding in the future due to their proximity to the wetlands he indicated that some of the units would have basements provided they can be “drained to daylight.” Others would be constructed on concrete slabs. He also noted that most of the units would have one garage bay located within the perimeter of the buildings on the first floor, reducing the need for surface parking by one space for each of these units. It remains unclear to me how large construction equipment can operate very close to wetlands without harming them. It appears some of the units would be located within twenty feet of the wetlands.

Gazette: “Council adopts wetlands ordinance”

At-large City Councilor James M. Dostal proposed an amendment Thursday that called for increasing the 10 feet no-encroachment zones in urban residential districts to 50 feet because of serious concerns about homes flooding, saying “We shouldn’t be building there…”

Adam Cohen, of North Street and an organizer of the North Street Neighborhood Association said he believes a 50-foot no-[en]croachment zone would be better for the city’s urban residential districts. That, he said, represents “consumer protection for homeowners.”

The Republican: “Wetlands ordinance approved”

The North Street Neighborhood Association, which has expressed concern about a proposed project by developer Douglas A. Kohl, previously presented the council a report it commissioned by Hyla Ecological Services Inc. of Concord, recommending a minimum buffer of 50 feet between wetlands and development to guard against flooding…

At-Large Councilor James M. Dostal, who opposed the ordinance along with Ward 7 Councilor Raymond W. LaBarge, said he was concerned about flooded basements and people being flooded out in concentrated development areas near downtown.

Alex Ghiselin, Letter to Gazette: “Don’t let development encroach on our wetlands”

The failure of the storm water system built as a part of the Northampton High School renovation six years ago illustrates why protecting wetlands is so important. Silt has filled the retention pond so there is no capacity to slow a storm surge which now flows unimpeded into the Mill River and contributes to flooding downstream. This accumulated silt also raised the water table and spills ground water into nearby basements…

Without maintenance, these [storm water mitigation] systems are part of the problem, not the solution…

Wetlands do not need to be maintained; they just need to be protected.

Carlon Drive: Compensatory Wetland Not Working

Mike Kirby writes:

In Carlon Drive, they simply scooped out a hole in the swamp-bottom, and called it a detention structure. Today it is just a pond, and a stagnant smelly one. It was designed to have a dry forebay, and a shallow main chamber was supposed to have only about 6 inches of water in it. This was supposed to be a compensatory wetland, full of cattails and wildflowers. A rock check dam was supposed to hold back the “first flush” off the parking lots and trap pollutants, and outflow from it was supposed to feed the wet part of the detention pond. Here rain water pouring off the new parking areas and street was supposed to be stored, and discharged safely.

That was the plan. Today if you stand by the pond and look down into it, you’ll see the check dam is now about two feet underwater. You can’t even see where they planted the marshgrass and flowers. The area is under water. Even in a fairly dry summer, the detention pond is only about a foot and a half from the t

op of the bank. There’s no storage to speak of, no discharge, no filtering. As it is constructed now, grey water from the parking lots and the access street goes directly into the swamp and the Connecticut River.

Connecticut River Watershed Action Plan: Remove impervious surfaces within 50 feet of streams

To reduce nonpoint source pollution from stormwater runoff, the Connecticut River Strategic Plan proposes the removal of impervious surfaces within 50 feet of streams and the investigation of “functional replacements” (such as the use of permeable pavement) for impervious surfaces within 100 feet of streams, in developed areas (PVPC, 2001). In the urbanized areas, the removal or retrofitting of impervious areas and the implementation of Stormwater Best Management Practices (BMPs) could be beneficial in improving water quality.

Photos Show: Man-Made Lakes and Stormwater Retention Systems Are No Substitute for Natural Wetlands

FEMA Community Rating System

Northampton was most recently rated (PDF) on 5/1/03. It was assiged to class 8. There are 10 classes, with Class 1 being the best. Class 8 communities enjoy a premium reduction of 10% on their flood insurance in Special Hazard Flood Areas. Class 1 communities enjoy a 45% reduction. The CRS classes for local communities are based on 18 creditable activities, organized under four categories:

- Public Information,

- Mapping and Regulations,

- Flood Damage Reduction, and

- Flood Preparedness.

(To be fair, only one city in Massachusetts is in a better CRS class than Northampton: Quincy, in class 7.)