The University of Massachusetts Press (Amherst) recently published Preserving and Enhancing Communities: A Guide for Citizens, Planners, and Policymakers, a timely addition to the Sustainable Northampton debate. The book generally supports Smart Growth concepts while it also underscores the value of urban open space. We focus on the latter in these excerpts from Chapter 10, “Natural Land: Preserving and Funding Open Space” (p.134-143):

See also:

The New Draft Sustainable Northampton Plan: Balancing Compact Growth Against Taxes, Urban Greenspace, Homeowner Preferences

An objective of the Plan is to “implement ideas for maximizing density on small lots”. (p.16) It calls for the City to “consider amending zero lot line single family home to eliminate 30′ side yard setback”. (p.69) It suggests the zoning laws be changed to “encourage single family homes in Urban Residential zoning districts by significantly reducing minimum frontage/lot width, for projects meeting form-based coding”. (p. 71)

These changes have the potential to reduce or eliminate the yards that separate homes from each other and from streets. This loss of greenspace may well entail a loss of privacy, attractiveness, flood protection (through an increase in impervious surfaces), and an increase in the heat island effect, noise and congestion. If fewer trees are shading homes, cooling costs are likely to rise…

Randal O’Toole: “The Folly of ‘Smart Growth'”

..Open space in valuable locations such as people’s backyards, urban parks, and golf courses will be transferred to less valuable locations such as private rural farms that are unavailable for recreation.

Bozeman Daily Chronicle: “Bozeman’s Growing Pains” (9/7/05)

Open space for recreation [in Portland] is at risk after 10,000 acres of parks, fields, and golf courses were rezoned for infill development.

Metro Portland’s Long Experience with Smart Growth: A Cautionary Tale

The notion that potential homeowners would prefer to pay the higher cost of high-density housing as an alternative to the traditional home/yard/neighborhood environment style of raising families

is wrong. The percentage of families moving to the Portland area that buy or rent within the UGB [Urban Growth Boundary] has fallen dramatically since site restrictions were implemented…

Berkeley, California: Cautions on Infill

In 1990, 60 percent of New Yorkers said they would live somewhere else if they could, and in 2000, 70 percent of urbanites in Britain felt the same way. Many suburbanites commute hours every day just to have “a home, a bit of private space, and fresh air.”

Northampton Redoubt: Urban Ecology, Planting Trees, and the Long-Term View

If we remove all of our in-town forested areas and wetlands they will likely be gone forever or at least a very long time. We would do well for posterity to err on the side of caution.

Seeing Like a State: Planning Gone Awry in the 20th Century

Cities tend to be complex organisms, Scott observes, so planners are constantly tempted to try to simplify their task:

Boston Urban Forest Coalition Aims to Plant 100,000 Trees

Downstreet.net: “Despite Tree City USA Honor Northampton Planting Lags”

Connecticut River Watershed Action Plan: Remove impervious surfaces within 50 feet of streams

Gazette opinion: “Don’t ease controls on wetlands” (10/25/07)

Proponents of Northampton’s new wetlands buffer zone regime, which authorizes development as close as 10 feet to wetlands in nine zoning districts, tried to reassure critics by saying developers wouldn’t automatically be entitled to get that close. The reality, however, is Northampton’s Conservation Commission will now be on the defensive whenever it asks developers for more than the minimum specified in the new ordinance. Alexandra Dawson, chair of Hadley’s Conservation Commission, writes in today’s Gazette [emphasis added]:

EPA: Urban Heat Islands

The term “heat island” refers to urban air and surface temperatures that are higher than nearby rural areas. Many U.S. cities and suburbs have air temperatures up to 10°F (5.6°C) warmer than the surrounding natural land cover.

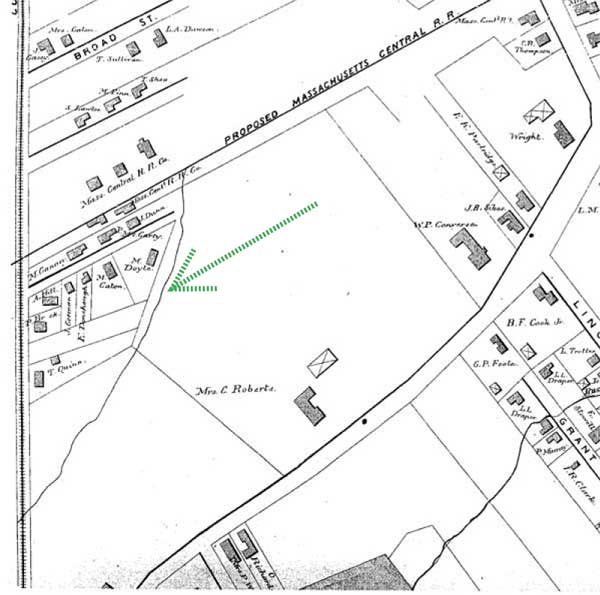

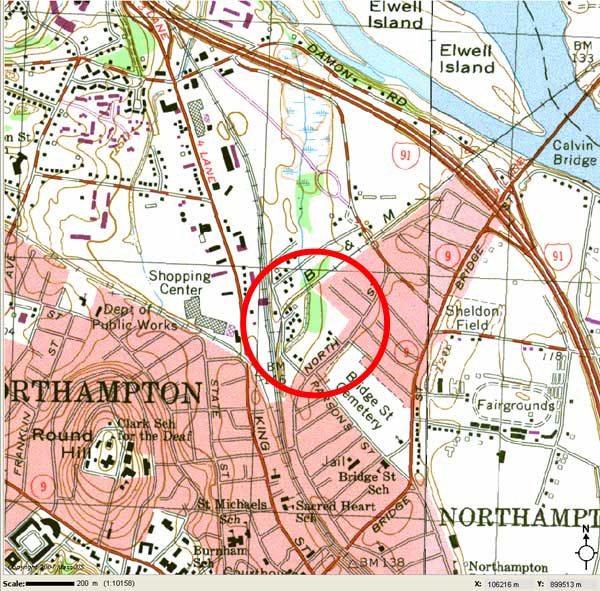

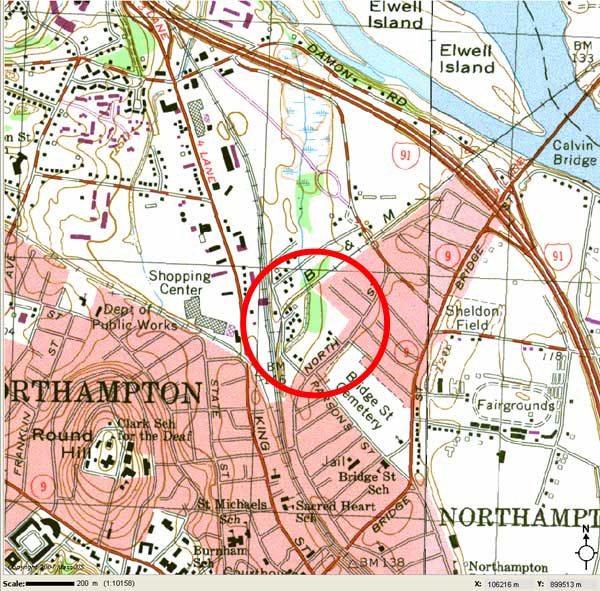

Topographical Map Shows How Kohl Condo Proposal Will Eat Into a Rare Stand of Mature Trees in Downtown

We have enlisted OLIVER, The MassGIS Online Data Viewer, to show just how rare and precious the woods behind North Street are in downtown Northampton. These woods are part of Kohl Construction’s proposed 5.49 acre condo site…

The following view dramatizes the considerable amount of impervious surface already in the area, especially around King Street and the Coca-Cola plant. Kohl’s “infill” project will convert a significant amount of the remaining greenspace to impervious surface. The presence of Millyard Brook shows that this area serves as a natural sink for water in the neighborhood.

Photo Essay: The Forest Behind View Avenue

…open space is a valuable and threatened commodity in many communities. In the state of Massachusetts alone, it is estimated that approximately 44 acres of open space are developed every day…

The benefits of preserving open space include protecting environmental quality and biodiversity, nurturing human health and well-being, preserving and enhancing community character and sense of place, and creating economic opportunities…

Undeveloped land is critical to maintaining clean water in streams, rivers, and other water bodies. In fact, studies have shown that as the percentage of developed land increases in a watershed, especially when over 25 percent of the area is buildings and pavement, there is [a] sharp decline in water quality and aquatic life (MacBroom 1998)…

Open space plays an important role in moderating the climate in urban areas. Street trees and other vegetation cool urban areas, which because of the high percentage of buildings and paving are much warmer than surrounding rural areas (Botkin and Keller 1995). Urban trees also remove dust and pollutants from the air. For example, research in Tucson, Arizona, estimates that “planting 500,000 desert-adapted trees over five years could be worth more than $236 million to the city” in the form of savings on air-conditioning and other costs (McPherson quoted in Lawson 1992, p. 42). In the city of Stuttgart, Germany, corridors of forest land have been preserved to provide a natural airflow through the dense urban environment, bringing clean air from the surrounding rural areas and diluting urban air pollution, as well as moderating the climate (Spirn 1984).

Protected open spaces are essential for human health and well-being. From the founding of the first urban parks, planners and landscape architects have recognized the recreational benefits of open space as a place for physical activity and restoration in crowded urban neighborhoods. The need to provide places for people to recreate is just as important today, especially as the sedentary lifestyle of many Americans including children has led to record levels of obesity and other health-related problems (Wilson 2002; Trails and Greenways Clearinghouse, undated; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 1996). Parks and trails provide opportunities for people to improve their physical health…

Preserving areas of nature, open space, and trees and other vegetation can have psychological as well as physical health benefits for local residents. There is a growing body of research which points to the power of nature to restore people from the stress of modern life, including mental fatigue (Kaplan, Kaplan, and Ryan 1998; Frumkin 2001). The positive benefits of nature have been found in a range of settings and populations, including hospital patients’ recovery from surgery, office workers’ productivity and job satisfaction, children’s ability to concentrate and do well in school, especially those with Attention Deficit Disorder, and even prisoners’ health and behavior (Frumkin 2001; Ulrich 1984; Taylor et al. 2001; and Moore 1981). Urban trees can also have a positive impact on building community in inner-city neighborhoods (Kuo et al. 1998). Many residents do not need these scientific studies to persuade them–people appreciate nearby green spaces as places to enjoy after a hectic day at work.

Protecting open space is often about protecting what makes a community special and unique… At the small-town or village scale, a forested hillside or surrounding farmland helps create a unique sense of place. Furthermore, preserving open space helps to create distinct edges that stop the blurring of community boundaries that is characteristic of urban sprawl. Defining what is unique about one’s community and identifying places that are special to local residents is an important part of the overall planning process (Hester 1990)…

While quality-of-life issues such as community character can be difficult to define, they are nonetheless important factors in individual and corporate economic decisions. In other words, open space sells. Homebuyers are willing to pay a premium for homes adjacent to parks, nature preserves, golf courses, lakes, rivers, and beaches. Communities are rated high as places to move or retire to based on many factors, including the percentage of parks and other open space amenities. Corporations consider quality-of-life issues for their employees when evaluating where to expand their businesses. Public investment in parks and open space has been found to provide a strong economic generator for municipal coffers in the form of increased property values for private land adjacent to parks and open space and economic investment by the private sector (Garvin 1996)…

…communities need to balance the need for new housing and the desire to preserve open space… preserving open space makes economic sense for many communities because it puts less of a burden on municipal services than do other types of development, particularly residential development. New residential development often costs more in municipal services (e.g., schools, police, fire protection) than it generates in tax revenue, and thus can be a net drain on local revenues. Open space including farmland requires much less in municipal services than it generates in taxes and is a net gain for many communities. In fact, a study of seven Massachusetts towns found that tax rates were much lower in rural areas with abundant open space than in more developed areas (Trust for Public Land 1999)…

Greenways are very efficient from a land protection viewpoint, because they protect linear corridors of open space, such as river valleys, which are often the only remaining open space in many developed areas. Stream corridors, in particular, often have the highest ecological value and are in many cases unsuitable for development…

See also:

The New Draft Sustainable Northampton Plan: Balancing Compact Growth Against Taxes, Urban Greenspace, Homeowner Preferences

An objective of the Plan is to “implement ideas for maximizing density on small lots”. (p.16) It calls for the City to “consider amending zero lot line single family home to eliminate 30′ side yard setback”. (p.69) It suggests the zoning laws be changed to “encourage single family homes in Urban Residential zoning districts by significantly reducing minimum frontage/lot width, for projects meeting form-based coding”. (p. 71)

These changes have the potential to reduce or eliminate the yards that separate homes from each other and from streets. This loss of greenspace may well entail a loss of privacy, attractiveness, flood protection (through an increase in impervious surfaces), and an increase in the heat island effect, noise and congestion. If fewer trees are shading homes, cooling costs are likely to rise…

Randal O’Toole: “The Folly of ‘Smart Growth'”

..Open space in valuable locations such as people’s backyards, urban parks, and golf courses will be transferred to less valuable locations such as private rural farms that are unavailable for recreation.

Bozeman Daily Chronicle: “Bozeman’s Growing Pains” (9/7/05)

Open space for recreation [in Portland] is at risk after 10,000 acres of parks, fields, and golf courses were rezoned for infill development.

Metro Portland’s Long Experience with Smart Growth: A Cautionary Tale

The notion that potential homeowners would prefer to pay the higher cost of high-density housing as an alternative to the traditional home/yard/neighborhood environment style of raising families

is wrong. The percentage of families moving to the Portland area that buy or rent within the UGB [Urban Growth Boundary] has fallen dramatically since site restrictions were implemented…

Berkeley, California: Cautions on Infill

In 1990, 60 percent of New Yorkers said they would live somewhere else if they could, and in 2000, 70 percent of urbanites in Britain felt the same way. Many suburbanites commute hours every day just to have “a home, a bit of private space, and fresh air.”

Northampton Redoubt: Urban Ecology, Planting Trees, and the Long-Term View

If we remove all of our in-town forested areas and wetlands they will likely be gone forever or at least a very long time. We would do well for posterity to err on the side of caution.

Seeing Like a State: Planning Gone Awry in the 20th Century

Cities tend to be complex organisms, Scott observes, so planners are constantly tempted to try to simplify their task:

Once the desire for comprehensive urban planning is established, the logic of uniformity and regimentation is well-nigh inexorable. Cost effectiveness contributes to this tendency… [E]very concession to diversity is likely to entail a corresponding increase in administrative time and budgetary cost… (p.141-142)In Northampton, the simplification du jour appears to be a drive to segregate our open space to the periphery, while weakening greenspace preservation in the more urban districts where it is already scarce.

Boston Urban Forest Coalition Aims to Plant 100,000 Trees

Downstreet.net: “Despite Tree City USA Honor Northampton Planting Lags”

Connecticut River Watershed Action Plan: Remove impervious surfaces within 50 feet of streams

Gazette opinion: “Don’t ease controls on wetlands” (10/25/07)

Proponents of Northampton’s new wetlands buffer zone regime, which authorizes development as close as 10 feet to wetlands in nine zoning districts, tried to reassure critics by saying developers wouldn’t automatically be entitled to get that close. The reality, however, is Northampton’s Conservation Commission will now be on the defensive whenever it asks developers for more than the minimum specified in the new ordinance. Alexandra Dawson, chair of Hadley’s Conservation Commission, writes in today’s Gazette [emphasis added]:

I thoroughly agree with recent comments to the effect that this is not the time to weaken local controls over development in or near wetlands. Few cities and towns outside Route 495 have local wetlands protection ordinances and bylaws; so what happens to one is likely to happen to others. This is clearly what has happened in Northampton and Greenfield…Northampton Open Space Plan: “This loss of habitat and natural flood buffering areas is Northampton’s most serious environmental problem”

…Northampton has adopted changes to its bylaws that limit the setback between development and wetlands in the business district to 10 feet, although it is obvious that 10 feet is not even enough space to accommodate the big yellow machines that do the building. It is true that a recent court decision indicates that wetlands ordinances (or conservation commission regulations adopted under them) should enumerate setbacks so that builders need not guess what will be required of them. Unfortunately, there is also case law stating that whatever is so established limits the commission’s discretion to ask for more unless there is a specific showing of why one proposal stands out from the others. If the setback in the ordinance is 10 feet, it will be very hard for the commission to justify a permit restricting building for 50 feet. For this reason, most eastern Massachusetts bylaws that contain setbacks start at 25 to 50 feet.

EPA: Urban Heat Islands

The term “heat island” refers to urban air and surface temperatures that are higher than nearby rural areas. Many U.S. cities and suburbs have air temperatures up to 10°F (5.6°C) warmer than the surrounding natural land cover.

The heat island sketch pictured here shows a city’s heat island profile. It demonstrates how urban temperatures are typically lower at the urban-rural border than in dense downtown areas. The graphic also show how parks, open land, and bodies of water can create cooler areas.

Topographical Map Shows How Kohl Condo Proposal Will Eat Into a Rare Stand of Mature Trees in Downtown

We have enlisted OLIVER, The MassGIS Online Data Viewer, to show just how rare and precious the woods behind North Street are in downtown Northampton. These woods are part of Kohl Construction’s proposed 5.49 acre condo site…

The following view dramatizes the considerable amount of impervious surface already in the area, especially around King Street and the Coca-Cola plant. Kohl’s “infill” project will convert a significant amount of the remaining greenspace to impervious surface. The presence of Millyard Brook shows that this area serves as a natural sink for water in the neighborhood.

Photo Essay: The Forest Behind View Avenue

Maps: Millyard Brook and Surrounding Wetlands a Longstanding Feature of Ward 3