Email in**@********oc.org for more information

Northampton, MA Citizens Campaign to Protect Their Urban Wetlands, Prevent Flooding

Citizens of Northampton, MA are campaigning to preserve the buffer zones around the city’s urban wetlands from development. Northampton has a proud tradition of environmental stewardship and sustainable growth, but on October 4, Northampton’s City Council plans to vote on an ordinance that would slash the no-build zone around wetlands to as little as 10 feet in many districts. The North Street Neighborhood Association this week is mailing 16,978 postcards to virtually all the registered voters of Northampton. The postcards call for maintaining 50-foot no-build buffers, the general standard to this point, to mitigate flooding, prevent water pollution, and keep neighborhoods green and cool.

Northampton, MA (PRWEB) September 28, 2007 — On October 4, Northampton’s City Council plans to vote on an ordinance that would slash the no-build zone around wetlands to as little as 10 feet in many districts. Up to this point, 50 feet has been the general standard, with limited exceptions. Citizens are concerned that the new rules will increase the risk of urban flooding and water pollution, and decrease the attractiveness of in-town living.

A review of the municipal wetlands regulations posted by the Massachusetts Association of Conservation Commissions indicates that authorizing building as close as 10 feet to wetlands is rare among Massachusetts communities. This permissive stance is at odds with a city that otherwise values environmental protection. In 2001, the Northampton City Council voted for the city to join the Cities for Climate Protection Campaign, a project of the International Council on Local Environmental Initiatives. In 2005, Northampton received a “Tree City U.S.A. Designation”. The current draft of Northampton’s Sustainability Plan, initiated by the city in 2005, affirms Northampton’s commitment to “Leadership in the advancement of sustainable practices that manage land use for long-term benefits…and improve our impact on the environment.”

The proposed new wetlands rules have been before the city for about two years, yet those who stand to lose the most from this ordinance have not been well heard. These are ordinary citizens who reside in the more densely populated area of Wards 1-4, plus parts of Ward 5. These zones–about 15% of Northampton’s land area–contain a disproportionately large percentage of Northampton’s homes.

Wetlands are a key component of Northampton’s natural drainage systems. The extensive flood damage Northampton suffered under Tropical Storm Floyd in 1999 showed that the city’s stormwater management systems are stretched even under its current wetlands policy. The proposed ordinance threatens to dramatically ratchet up the pressure on many of Northampton’s in-town wetlands.

Hyla Ecological Services of Concord, MA recently evaluated the likely impact of relaxing Northampton’s wetlands buffer zone regulations. Hyla reports:

“Buffers of less than 50 feet in width are generally ineffective in protecting wetlands. Buffers larger than 50 feet are necessary to protect wetlands from an influx of sediment and nutrients, to protect wetlands from direct human disturbance, to protect sensitive wildlife species from adverse impacts, and to protect wetlands from the adverse effects of changes in quantity of water entering the wetland… (Castelle et al., ‘Wetland Buffers: Use and Effectiveness’, 1992)

“Buffer function was found to be directly related to the width of the buffer. Ninety-five percent of buffers smaller than 50 feet suffered a direct human impact within the buffer, while only 35% of buffers wider than 50 feet suffered direct human impact. Human impacts to the buffer zone resulted in increased impact on the wetland by noise, physical disturbance of foraging and nesting areas, and dumping refuse and yard waste. Overall, large buffers reduced the degree of changes in water quality, sediment load, and the quantity of water entering the adjacent wetland.” (Castelle et al., 1992)

To alert citizens to act, the North Street Neighborhood Association this week is mailing 16,978 postcards to virtually all of the city’s registered voters. The association is composed of local citizens concerned for the environment and the quality of in-town living. The postcard asks voters to call on their City Councilors to stand up for urban greenspace and prevent flooding. The text of the postcard is published at NorthAssoc.org.

The proposed ordinance aims to encourage “infill development”, preserving open space outside of already built-up areas. However, citizens cannot be expected to want to move into the city’s denser areas if the long-term safety and attractiveness of these areas are in doubt. When the green buffers around urban wetlands are sacrificed to development, citizens can expect their neighborhoods to become hotter, more polluted, and more flood-prone. Encroaching on wetlands is not a sustainable path to growth. (Sources: EPA: Heat Island Effect; EPA: Wetlands: Protecting Life and Property from Flooding; Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation)

Adding substantial amounts of impervious surface within 50 feet of wetlands goes against Northampton’s Flood Mitigation Plan, which was approved by the City Council in 2004. In a table of Existing Mitigation Strategies, the plan cites as one “effective” strategy a “100 foot buffer around wetlands and the wetland resource area itself…” One of the “Priority Actions” recommended by the plan is to “Consistently enforce the Wetlands Protection Act to maintain the integrity of the 200′ riverfront area, wetlands and wetland buffer areas.”

The proposed new rules also go against Northampton’s Open Space Plan, approved by the City Council in 2005. Referring to the impact of development in local wildlife habitats, the plan states, “This loss of habitat and natural flood buffering areas is Northampton’s most serious environmental problem.”

The association calls on Northampton’s City Council to insist on a minimum 50-foot no-disturbance buffer around all our city’s wetlands. At the very least, residential districts need more than the meager flood protection afforded by 10-foot buffers. Springfield requires 50 feet, as do many other Massachusetts communities. Northampton deserves no less.

Learn more about how wetlands and their buffer zones benefit communities at the North Street Neighborhood Association website, NorthAssoc.org.

###

Postcard as mailed to voters:

[September 30 update: The phone number published on the Northampton City Council web page for Ward 3 Councilor Marilyn Richards has been disconnected. We encourage citizens to contact her at her public email address, jo*****@*****st.net. You may also leave a message for her with Lyn Nuttelman Simmons, Clerk to the Council, at 587-1210.]

Other citizen outreach efforts include this ad in Friday’s Daily Hampshire Gazette…

…and 30-second radio sp

ots airing on WHMP-AM’s morning talk shows:

On October 4, Northampton’s City Council may approve a wetlands ordinance that opens up

much of our remaining urban greenspace to development. Wards 1 through 4 are at particular

risk of becoming hotter, more polluted, more congested, and more likely to flood. Ask your

councilor to insist on a minimum 50-foot no-build zone around all our wetlands. Paid for by the

North Street Neighborhood Association. Learn more on the web at NorthAssoc.org. That’s N-

O-R-T-H-A-S-S-O-C dot O-R-G.

Listen to the spot as an mp3 file.

See also:

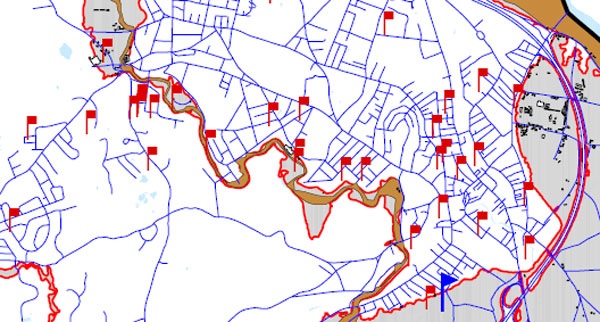

Flooding is already affecting Northampton’s built-up areas during major storms. Weakening wetlands buffer zone requirements downtown will make this worse

[Flood damage reports from Tropical Storm Floyd pepper downtown Northampton (1999). Note most of the red flags are outside the traditional 100-year floodplain. This is a sign that Northampton’s stormwater management systems are stretched even under the existing wetlands buffer zone regime. We object to ratcheting up the pressure on our in-town wetlands, a key part of our natural drainage system.]

EPA: Wetlands and Flood Protection

Wetlands function as natural sponges that trap and slowly release surface water, rain, snowmelt, groundwater and flood waters. Trees, root mats, and other wetland vegetation also slow the speed of flood waters and distribute them more slowly over the floodplain. This combined water storage [and] braking action lowers flood heights and reduces erosion. Wetlands within and downstream of urban areas are particularly valuable, counteracting the greatly increased rate and volume of surface-water runoff from pavement and buildings…

A one-acre wetland can typically store about three-acre feet of water, or one million gallons. An acre-foot is one acre of land, about three-quarters the size of a football field, covered one foot deep in water. Three acre-feet describes the same area of land covered by three feet of water.

The Economic Value of Wetlands: Wetlands’ Role in Flood Protection in Western Washington

Development practices that eliminate or compromise natural systems capable of controlling runoff appear to be exacerbating flooding problems in many areas. This highlights the importance of the remaining natural systems capable of attenuating flood flows, particularly wetlands, in the region’s defenses against increasingly destructive floods…

More than half of the wetlands that once existed in western Washington have been lost. Often the cause has been agricultural conversion, but today wetlands are increasingly at risk due to urban and suburban development. Western Washington is now one of the fastest growing regions of the country, and the remaining wetlands in rapidly developing areas are increasingly valuable for the flood protection they can provide. At the same time, the increasing pace and density of development is resulting in the natural wetlands systems that are capable of absorbing urban runoff becoming ever more fragmented, even as the need for flood protection grows ever more critical…

EPA: Urban Heat Islands

The term “heat island” refers to urban air and surface temperatures that are higher than nearby rural areas. Many U.S. cities and suburbs have air temperatures up to 10°F (5.6°C) warmer than the surrounding natural land cover.

The term “heat island” refers to urban air and surface temperatures that are higher than nearby rural areas. Many U.S. cities and suburbs have air temperatures up to 10°F (5.6°C) warmer than the surrounding natural land cover.The heat island sketch pictured here shows a city’s heat island profile. It demonstrates how urban temperatures are typically lower at the urban-rural border than in dense downtown areas. The graphic also show how parks, open land, and bodies of water can create cooler areas.

Northampton Redoubt: Urban Ecology, Planting Trees, and the Long-Term View

If we remove all of our in-town forested areas and wetlands they will likely be gone forever or at least a very long time. We would do well for posterity to err on the side of caution. For example the cost estimate to restore part of the downtown historic Mill River channel runs into the millions of dollars. Had the river’s diversion in the 1940s been handled differently, perhaps with a sharper eye towards the future, maybe today we wouldn’t be searching for dollars to make its restoration a reality.

The proposed ordinance is not consistent with past practice, and favors substantial new encroachments on Northampton’s wetlands

Is the Proposed Wetlands Ordinance Similar to Current Buffer Zone Policy? Judge for Yourself

Photos Show: Man-Made Lakes and Stormwater Retention Systems Are No Substitute for Natural Wetlands