Professor Philip Bess of Notre Dame gave the opening presentation of Design Northampton Week this evening to an intent crowd at Northampton’s Senior Center. The presentation lasted a little over two hours. We’ll do our best to make our video of the event available within a day or two.

This handout provided by Notre Dame (PDF) includes “Ten Characteristics of Good Traditional Towns and Neighborhoods”, “What’s Wrong With Sprawl?”, “The Rural-to-Urban Transect”, “What Is a Charrette?”, “Charter of the New Urbanism”, and “The Asphalt Rebellion: Vibrant and beautiful, not fast and ugly”.

Professor Philip Bess

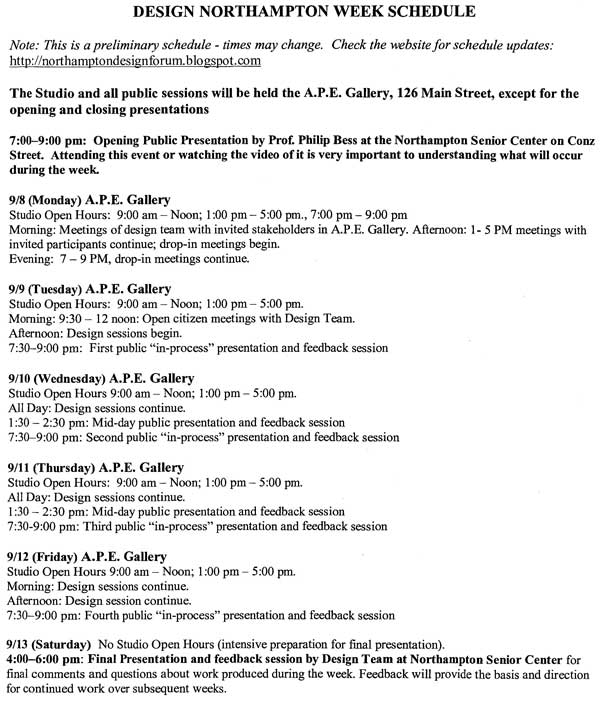

If you have trouble reading the hours for public input, design presentations and feedback sessions, they are also provided here, or see the full schedule below:

Helping to launch Northampton Design Week were Ward 3 City Councilor Bob Reckman, Mayor Clare Higgins and Northampton Design Forum chair Joel Russell…

See also:

Public Input Hours and Presentations at Design Northampton Week

Video: Notre Dame Urban Design Studio Presentation

Notre Dame Pitches Urban Design Studio to Northampton

[NSNA comments:] …sprawl happens because we have electricity, phones, cars, a growing population and widespread wealth (PDF). In particular, we have discussed the many concrete benefits of owning a vehicle. When people have a chance to escape crowded environments that lack greenspace, many will do so,

especially if they have young children. Living miles away from a city

center used to be isolating. Modern technology means that’s no longer

the case.

There are certainly aspects of sprawl that merit criticism, but planners and scholars need to understand why so

many people like detached homes, private yards and private cars. It’s

not just that they’ve been bamboozled by advertising or victimized by

conspiratorial car companies. Too often New Urbanists will insist that

dense development and mass transit are the only hope for a

resource-constrained future, when other solutions, such as more efficient cars and smaller (yet still detached) homes may prove to be more popular, and thus more workable. Popular solutions are less likely to require large government subsidies, cause voter dissatisfaction, or spur leapfrog sprawl…

Books & Culture: “The Life of Trees” (July/August 2008)

…Treeless urbanity seems horrible to us—the elimination of greenery is a key feature of almost all our dystopian images—but it must be remembered that in the Middle Ages cities were very small places indeed. Paris was probably the largest European city of that period, and you could walk from any one of its walled boundaries to any other in half an hour. So, though there was an absolute divide between the treeless city and the forested countryside, marked by any given city’s walls, the countryside could be almost instantly reached by anyone ambulatory.

The practice of planting trees in European cities only began to grow

once cities got larger and the countryside grew correspondingly more

distant. In the 17th century the great diarist, gardener, and

arboriphile John Evelyn visited Antwerp, whose leaders had,

half-a-century earlier, planted trees along the whole length of the

elevated city walls. “There was nothing about this City,” Evelyn

rhapsodized, “which more ravished me than those delicious shades and

walks of stately Trees, which render the incomparably fortified Works

of the Town one of the sweetest places in Europe.”

…By the nineteenth century it had been agreed, in most cities of the

world, that trees are both beautiful and health-giving, and that

therefore trees should be planted anywhere in our cities where it is

possible to plant them. As we still do…