Randal O’Toole of the Thoreau Institute has kindly allowed us to share his photo tour of Oak Grove, Oregon. Oak Grove, a suburb of Smart Growth stronghold Portland, decided in favor of preserving the pleasant community they knew over gambling on densification. Oak Grove’s population is about 12,800 inhabiting an area of 3.2 square miles (Wikipedia).

Towards the end of the tour, strip malls are discussed. The North Street Neighborhood Association is not necessarily in favor of strip malls, vast ugly parking lots, and unwalkable environments. However, planners must be careful that what they try to replace them with is actually a viable improvement. They also need to respect the utility and convenience of the private automobile. If congestion and a lack of parking make it hard to drive, people will often choose to live elsewhere rather than give up their cars. This can make sprawl worse.

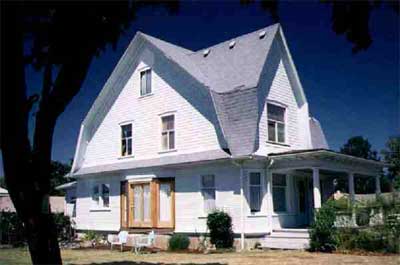

Oak Grove is a suburb of Portland that started more than a century ago, when the nation’s first interurban electric rail line connected Portland with Oregon City. People began building large homes on large lots along the rail line, and a community sprang up.

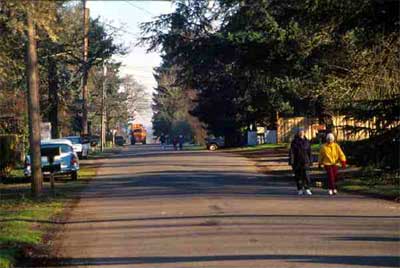

Over the years, many of the lots have been broken up, but in some areas, as here, they average more than a third of an acre in size and some are more than an acre. This means the area has very low densities and, in turn, not much automobile traffic.

Oak Grove remains unincorporated and thus under the jurisdiction of Clackamas County. In 1995, county planners came to the neighborhood and said they wanted to rezone the area to make it easier to walk around and ride bicycles. There are no sidewalks in the area, but because the area is so low in density, people do not hesitate to walk or ride bicycles.

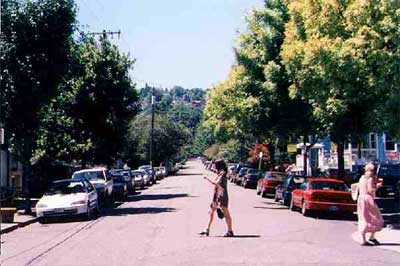

This is a denser part of Oak Grove, where many of the houses are on 5,000-square-foot lots (about eight houses per acre). Even here, auto traffic is so low that there is little conflict between walking and driving.

Once a thriving retail area on the rail line, downtown Oak Grove declined after a major highway was built about a mile to the east of the rail line in the 1930s. Major stores located on the highway and today the rail line is gone and downtown Oak Grove contains an assortment of shops and light industry.

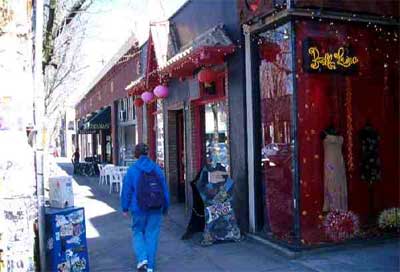

Planners wanted to “revitalize” downtown by allowing four- to five-story apartments with retail and commercial shops on the ground floors. We asked planners what part of the Portland area looked most like their vision for the future of Oak Grove. They said, “Northwest 23rd Avenue, where people are learning to walk and ride transit more.”

Northwest 23rd Avenue has many popular shops and boutiques. Hobson Johnson, local real estate consultant, says that people in the area are learning to walk more, mainly because they can’t find parking within a few blocks of their destinations.

Northwest 23rd has many cute shops. But these shops cannot survive on walk-in business alone. So they work to attract people from all over the city. Of course, most of those people drive, creating huge traffic jams and parking problems.

The real estate consultant added that parking shortages created major conflicts between businesses and residents of side streets, such as the one shown here. Residents often found that they were unable to park near their homes. Businesses insisted they needed parking on the side streets or they would lose their customers.

The street I lived on is a couple of blocks from downtown Oak Grove. Planners wanted to rezone everything on the right side of the street to 24-unit-per-acre apartments and everything on the left to 5,000-square-foot lots. This would have been three to eight times denser than it is today.

This house on the right side of the street must have particularly offended planners. Because it has a garage in front of the rest of the house, they call it a “snout house.” People with garages in front drive more and have less of a sense of community than people with garages in back. At least, that’s what leading planners and architects say, though there is no evidence for it and I think they just make this stuff up.

Here are some high-density apartments of the sort that planners had in mind to replace the snout houses on the east side of the street I lived on. These apartments have plenty of parking in back, but people still park in front for convenience. Of course, most of the street I lived on already has houses, so new apartments would appear as infill rather than as one big complex.

Planners proposed to use minimum-density zoning, making it illegal to build one house on a one-acre vacant lot. Instead, if a landowner built anything at all, they would have to build at least seven houses on the acre if it were zoned for 5,000-square-foot lots and at least a 20-unit-per-acre apartment if it were zoned for 24 units per acre. This would lead to high-density infill in a low-density neighborhood, as is happening in this Gresham neighborhood, which received such zoning several years ago.

The Creighton house is one of the oldest homes in Clackamas County. Just a block from downtown, it was to be rezoned for high-density, mixed-use development. “To preserve the historic character of the area,” said one of the planners, “we will zone for zero-foot setbacks.” That meant that new construction would front directly on the street.

Planners may have expected that the Creighton house would be developed similar to the Standard Dairy, an older building in Portland that was turned into a high-density, mixed-use development. You can barely see the outlines of the original building today.

This large stone house is unusual for the Portland area, where abundant timber has led to mostly wood construction. But a family of stone masons who helped build the famous Columbia River Highway settled in Oak Grove and built many such stone homes. This house is on a street that planners zoned for high-density, mixed-use developments.

Perhaps this is what planners had in mind for the stone house. The Belmont Dairy, in Portland, is based on an older building and now contains parking and shops on the ground floor and four stories of apartments above. The outlines of the older building are no longer visible.

When we protested that we did not want to be densified as planners intended, they told us that if we didn’t let them rezone Oak Grove now, Metro would require them to rezone us to higher densities later. Metro is Portland’s regional planning agency and it gave population targets to Clackamas County and all of the cities in the Portland area. Planners were required to rezone neighborhoods to meet their population targets.

Metro’s office building, shown here, is a former Sears department store. Rather than tear the building down and build a new one, which would have cost $15 million, Metro proved their planning skills by recycling the old Sears building — at a cost of $30 million.

In addition to some vacant lots that are sometimes as large as an acre, there are still some farms in the Oak Grove area. Farmers grow berries and other produce and sell them to local residents.

Planners have rezoned many of these farms for high-density, transit-oriented development. This particular farm is near the light-rail line in Gresham. To meet Metro’s population targets, county planners hope that Oak Grove farmers will soon develop their farms to high densities as well.

The Top o’ Scott Golf Course is located in Clackamas, another unincorporated part of Clackamas County a few miles from Oak Grove. It was zoned as open space in 1980. But to meet Metro’s population targets, county planners rezoned two-thirds of it for high-density residential and commercial development in 1999.

Oak Grove residents protested loudly enough that the Clackamas County Commission asked Metro to take Oak Grove off of its list of neighborhoods to be densified. Metro did so. But dozens of other neighborhoods weren’t so lucky. This huge development was recently built in east Portland.

The problem is that people don’t want to live in high densities, especially when there are planner-induced parking shortages. A state regulation requires Portland to reduce its parking by 10 percent, so new developments are often built with limited parking. Since developers won’t build what they can’t sell, planners have to subsidize them to get them to build high-density developments.

This development next to a light-rail station in Beaverton received $10 million in subsidies, yet went broke before it was finished. Since it was to have limited parking, it is doubtful that it could have made any money even with the subsidies.

Residents won the battle of Oak Grove, but planners are not through yet. This is the major highway which replaced the rail line many years ago. Today it is lined with stores and strip malls which serve local residents well, but which planners regard as ugly because they provide so much parking. Planners want to turn the highway into a “boulevard,” with fewer lanes, slower traffic, and stores fronting on the street instead of separated from the street by parking lots.

Here is the same road in Portland, many miles north, which has been turned into a boulevard. The road has no right-turn lanes, so cars slowing to turn right must delay traffic behind them. Left-turn lanes are partially blocked by median strips. The few thriving businesses in this area have large parking lots on the side or in back; most other businesses are doing poorly.

The road does not serve the residential area as well as it does in Oak Grove, where it provides higher traffic flows, higher speeds, and access to a wider range of businesses. But planners like it better in Portland because, they think, driving is discouraged. Oak Grove residents are currently working to save their highway from being turned into a boulevard.

See also:

Randal O’Toole: “The Folly of ‘Smart Growth'”

Metro [Portland] wrote a plan that called for expanding the

urban-growth boundary by no more than six percent over the fifty-year

period. That meant that the population density inside the boundary

would increase by 70 percent…

The region’s cities and counties

encountered major opposition when they tried to rezone existing

neighborhoods to higher densities. One Portland suburb recalled its

mayor and two members of its city council from office after they

endorsed higher densities over local opposition. To meet their targets,

planners turned to rezoning farms and other open spaces as high-density

areas. One suburban county rezoned a golf course for 1,100 new housing

units and 200,000 square feet of office space. Ten thousand acres of

prime farmland inside the urban-growth boundary were also targeted for

development.

…despite the shortage of single-family housing, Portland residents have failed to embrace Metro’s high-density developments…

Although

the smart growth policies — high-density developments, light-rail

transit, limited freeway expansions, traffic calming, and parking

limits — are supposed to reduce per capita driving by 10 percent,

Metro’s own planners say that they will fail to meet that goal…

Even

with a five- or 10-percent reduction in per capita driving, the

projected 80-percent increase in population density assures that

Metro’s plan will greatly increase Portland-area congestion. Metro

predicts that the amount of time Portland-area residents waste sitting

in traffic will quintuple by 2020…

Randal O’Toole: “Debunking Portland: The City That Doesn’t Work” (PDF, Policy Analysis, 7/9/07)

When

judged by the results rather than the intentions, the costs of

Portland’s planning far outweigh the benefits. Planners made housing

unaffordable to force more people to live in multifamily housing or in

homes on tiny lots. They allowed congestion to increase to

near-gridlock levels to force more people to ride the region’s

expensive rail transit lines. They diverted billions of dollars of

taxes from schools, fire, public health, and other essential services

to subsidize the construction of transit and high-density housing

projects.

Those high costs have not produced the utopia planners

promised. Far from curbing sprawl, high housing prices led tens of

thousands of families to move to Vancouver, Washington, and other

cities outside the region’s authority. Far from reducing driving, rail

transit has actually reduced the share of travel using transit from

what it was in 1980. And developers have found that so-called

transit-oriented developments only work when they include plenty of

parking.

Randal O’Toole: “Dense Thinkers” (Reason Magazine, January 1999)

The

“decline” of cities that officials worry so much about is due to the

fact that cars, telephones, and electricity make it possible for people

to live in lower densities–and most choose to do so…

Metro Portland’s Long Experience with Smart Growth: A Cautionary Tale

Expected

home price inflation was found to be greater than expected in most of

the states that embraced smart growth, including Oregon, Washington,

Tennessee, Kentucky, Pennsylvania, and Colorado…

Restrictive

growth policies actually caused increased suburbanization in Portland,

which now has the 10th greatest suburbanization rate in U.S. As home

prices went up in the site-restricted metropolitan area, families moved

further out to find affordable housing…

There is very little

evidence that other aspects of restricted growth policies have reduced

households’ costs in other areas to offset the increased costs of

housing. In economic terms, it is safe to say that restricted growth

policies are not family-friendly…

Small cities surrounded by

developable land, like Eugene and Salem, now have housing prices that

rival those in San Francisco Bay Area communities, when the purchasing

power of local incomes is considered…

Oregon actually has a

tremendous amount of available land… Oregon has apparently

successfully engineered a shortage of sites in a state with plentiful

land…

New York Times: “Vibrant Cities Find One Thing Missing: Children”

After

interviewing 300 parents who had left the city, researchers at Portland

State found that high housing costs and a desire for space were the top

reasons…

Planetizen: “Trouble in Smart Growth’s Nirvana” (6/30/02)

The

2000 Census shows that, as expected, Portland became more dense. What

was not expected was that all-suburban Phoenix would become more dense

than Portland…

Despite the

claims of the transit-media complex, Portland’s anti-highway policies

are failing. The 2000 Census shows that transit’s work trip market

share remains 20 percent below the 1980 Census rate, which preceded

opening of the first light rail line. And, Portland’s highway

congestion has become the worst of any metropolitan area of its size…

Densification

is no more popular in Portland’s neighborhoods than it is in Berkeley,

Boulder or Bozeman. As a result, a recent citizen’s initiative sought

to limit Metro’s (the land use regulation agency) densification power…

LA Weekly: “City Hall’s ‘Density Hawks’ Are Changing L.A.’s DNA

The shift is pushing L.A. from its suburban model of single-family

homes with gardens or pools — the reason many come here — toward an

urban template of shrinking green patches and multistory buildings of

mostly renters…

Scrape-Off Redevelopments Provoke Backlash in Denver Neighborhoods

Supporters [of lower-density zoning] said the increased density from the multiple-unit structures

was ruining the character of the two neighborhoods, which are comprised

of predominately single-family detached homes.

The outcropping of multifamily structures has cast shadows on gardens,

increased traffic and created parking wars, among other quality of life

issues, they said…

“Sprawl and Congestion—is Light Rail and Transit-Oriented Development

the Answer?”

The allure of the automobile is compelling, and crafting a sensible

transportation policy requires an acknowledgement of the wonderful

attributes of the car:

The motor vehicle has enriched our

lives in countless ways. It has provided the easy connectivity that

enables modern, highly interdependent, urban societies to thrive. It

has eliminated rural isolation. It has enabled workers to choose

employers rather than accept whatever employment opportunities are

within walking or transit distance of their homes. The personal truck

allowed craftspeople and artisans to carry their tools with them and

enter the middle class by becoming independent contractors. The motor

vehicle has enabled people to live outside urban centers and still

participate in mainstream society.

The car is an amazing piece

of technology that has greatly extended our range of choice as to where

to live, work, shop, and play. No other form of transport can compete

with the automobile in terms of door-to-door mobility, freedom to time

one’s arrivals and exits, protection from inclement weather, and

comfort, security, and privacy while in transit.[2]

NY Times Magazine: “The Autonomist Manifesto (Or, How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Road)”

…the average commute by public transportation takes twice as long as the average commute by car…

Smart Growth Winners (Rich People) and Losers (Other People)

Smart growth is great if you can

afford to have everything you buy delivered, or are in excellent

physical condition with a physically undemanding job; it is not so

great if you have to come home from your shift at the nursing home to

lug groceries a quarter-mile down the street, and then up three flights

of stairs.

Grasping the Sustainable Northampton Vision: We Need Pictures

…Zoning has great advantages for specialists, namely lawyers and traffic

engineers, in that they profit financially by being the arbiters of the

regulations, or benefit professionally by being able to impose their

special technical needs (say, for cars) over the needs of citizens —

without the public’s being involved in their decisions.

Traditional

town planning produces pictorial codes that any normal citizen can

comprehend. This is democratic and ethical as well as practical. It

elevates the quality of the public discussion about development. People

can see what they’re talking about. Such codes show a desired outcome

at the same time that they depict formal specifications. They’re much

more useful than the reams of balderdash found in zoning codes.